Jeremy deBeer - The Role of Levies in Canada's Digital Music Marketplace

I like a good argument!

Jeremy deBeer argues that a levy is not the solution to the unlicensed use of digital music from a background of law and technology with some normative conclusions.

He prefaces his paper at this link with some background and some lead in material to hook you up to what you are going to get and not get, if you go on to read his "authoritative" -read, well documented- paper through the links he provides.

He does make a very important observation first:

"Parties not directly involved in the use of copyright-protected music have increasingly become the targets of established or proposed schemes to provide revenues for the music industry."

This is clear. But it is a long story perhaps not best left in entirely in his hands alone.

Are consumers at fault as non-professional users of copyrighted work, as they seek ways to use their final purchases differently than the intended use? The Theberge case in the Canadian Supreme Court did not seem to think so.

This case is a classic case where the artist thought that someone had infringed on his rights by making unauthorized copies from the gallery photographic plates (guidebooks) he authorized and made money on. He did not anticipate that someone would transfer those plates to canvas, one for one, and then sell those works, in effect competing with his own originals. The court found that he may have a moral rights case but not an infringement case, but to pursue his moral rights case he had to go before a court to argue that these works put his reputation at risk.

I should note, that the copies expostulated as to be infringing would be in no way comparable to the real work, nor did they contain his signature indicate that they were his, and would be of questionable value to an art affectionado. The court found in a split decision that this was "cool."

In my thinking, this is the same state of affairs as you find in a file sharing situation: the derivative copy is not quite the same as the original as generally speaking it is a degraded copy, compressed into a different format for transmission efficiency. That compression is not found on a commercial CD as there is no question that with a CD player there is not a bandwidth issue.

Should the recording industry pursue their moral rights in their works? Maybe. Infringement? I don't think so. Not in Canada.

Jeremy deBeer also sets up a background that is very hard to actually find in reality, in whatever age one looks at this music business:

"Traditional business models in the music industry have been built mostly upon the voluntary exchange of rights in a free market"

Voluntary exchange? Huh. If we are talking about money voluntarily surrendered for rights, yeah, no one is breaking arms to sign deals I think or blowing up factories or suing Aunt Martha, whoops, they are suing lil old ladies and kids. Thank G-d for Terry McBride, who heads Nettwerk Music Group, who is fighting no less the RIAA, and by association the CRIA, back here. Do the politicians get this picture??? We will see.

This is not the academic market: this is business and for every right imaginable, there is a rightsholder claimant, singular, joint, severable, assignable, waivable, and hanger-on, ad nauseum, who wants to be paid. One only has to leaf through the excellent tomb by Paul Sanderson "Musicians and the Law in Canada" or David Baskerville's "Music Business Handbook and Career Guide" to get very far away from any notion of voluntary exchanges. Do you need a lawyer, an agent, a manager, a publicist, or an inhouse lawyer and a retained law firm for a "voluntary" exchange?

On a final purchase, you might even need a lawyer to read an end user license (EULA) to accept after the fact a purchase of software or music, and then try to get back your money from your friendly retailer who says all sales of music and software are final, after you find your privacy is found to be traded or invaded, or your property is threatened (here, here, ...). A big sigh, to the late Anne Wells Branscomb for her prescient and great book "Who Owns Information?" (1994).

So I go forward into this article with a reluctance as the basis appears poisoned if one assumes a world of voluntary exchange amidst the legal profession's buffet feeding line here.

That said, I have now another reference to Daniel Gervais work in a similar vein, "Use of Copyright Content on the Internet: Considerations on Excludability and Collective Licensing" to find a solution for a problem that appears to me, to be a creation of the major recording companies themselves.

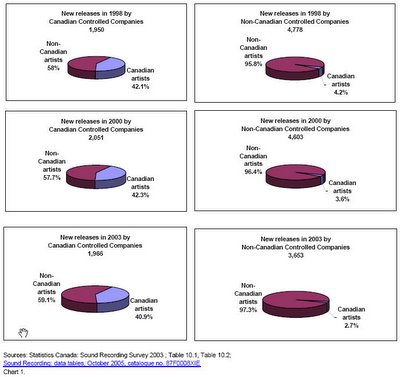

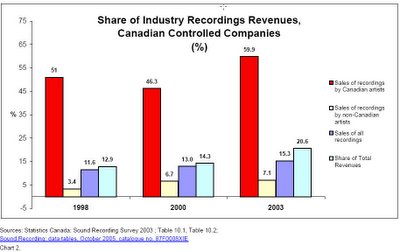

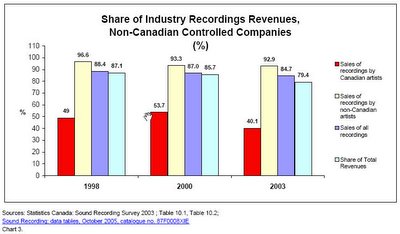

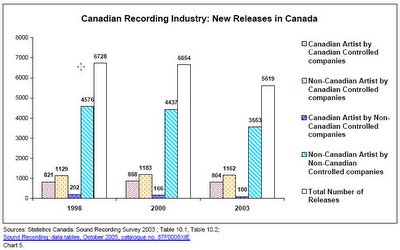

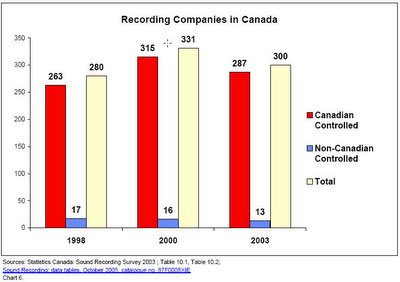

Why their problem? The majors consolidated. The majors did not anticipate final use. The majors did not respond in any timely way to the market demand for downloadable online music (in economic terms, they forced the production of "bad" music, as an imperfect substitute to the "good" music that they did not offer but was yet demanded). The majors do not in Canada promote Canadian artists to the extent of foreign artists yet Canadian recordings sell better in Canada (DOH!). They appear to cherry pick the independents, and then kill the expected extra output otherwise from the acquisition. All while crying to the government for help, using whatever means are available to them to make their case, including direct political donations to politicians.

On to the role of levies in Canada ...

Post-script: A Canadian company "Zunior" www.zunior.com, now offers 2 download types for each album it sells: the superior CD quality FLAC version, and for $2 less, the MP3 variant. If you have the ears, equipment and hard drive, FLAC versions very much demonstrate an express example to the overall point of this post: If the recording owners had provided quality downloads at reasonable prices would there be any issue at all about DRM? Frankly, I think the answer is no. Bad money chasing good with good not even showing up ... another reverse of Gresham's Law but with a twist.